My journey to teaching computer science, functionally

Table of Contents

I found myself in a cramped, unventilated phone booth when my dreams came true.

The bare WeWork call booth was dimly lit by my laptop, which displayed a Zoom waiting room. My leg bounced incessantly, mimicking the race of my heart. My mother had told me to stop doing that.

I was moments away from a meeting with a professor from Carnegie Mellon's School of Computer Science, to discuss my potential appointment as the summer instructor for 15-150, Principles of Functional Programming. At only 23 years old, I had only had a few job interviews in my life, and I felt woefully unprepared.

Should I have dressed formally, even in the laid-back tech hub of San Francisco, where the lack of a Patagonia jacket and converse would have made me stick out like a sore thumb? Should I have better prepared my shpiel on how much I wanted this opportunity?

I didn't have the right words. In that instant, I didn't know how I could possibly convey that I didn't just want it, I needed this job opportunity.

I couldn't tell anyone that this moment could either fulfill my dream or kill it outright.

Part 1: Becoming an instructor

At the time of writing of this blog post, I have just finished my summer teaching 15-150 as the instructor of record in the summer 2023 semester.

This was a long trial of months of preparation, late nights, emails, and back-breaking work that threatened to overwhelm me at times. In the wake of such a semester, I thought it would make a fitting first blog post, to record and review what happened and what I learned from this summer.

This is a story in multiple parts, but it starts with why it was so important that I obtain the job to teach functional programming. Why did it matter so much to me?

I don't have much of a connection to my extended family.

This is owed to, in part, by being the child of first-generation immigrants from China, and having an extended family that will never be able to read this article. Stories of my grandparents or cousins in China may as well have been written in a storybook, about characters of fiction. They are about equally as likely to have an impact on my life.

I have only one instance where I can remember putting stock in my connections to my more distant relatives. In high school, during a project to interview an elder relative, I discovered that my grandfather, similar to my father, had been a university professor.

I don't know that I put much stock in fate, but this felt like something similar. In my early years where I didn't know who I was, it seemed like a sign, like the universe had a role for me to fill after all. I could continue the legacy.

I was convinced, throughout much of college, that I wanted to be a professor. I wore clothes that I deemed to be "academic", buried my head in my studies, and fretted over silly things like my GPA or applications that I would end up never writing. I applied to be a teaching assistant and found teaching to be one of my greatest joys, returning to teach the course 15-150 six times over my undergraduate career.

Life seemed simple and clear-cut. Birds chirped, rain fell, and I was going to be a professor.

But, life, as it so often does, had other plans for me.

In my senior year, burned out by remote learning during COVID, and years of intense studying, I realized that I didn't want to pursue an academic career. I became disillusioned with research and the projects that seemed interesting on paper, but failed to motivate me to actually do the work. I disliked the research papers that seemed written by an elite club of people specifically to keep me out.

I called it quits, simply put, and took a job in the industry as a software engineer. By turning my back on a Ph.D, I said goodbye to my hopes of one day attaining an instructing position at the university level. I thought that was the end of it. A pivot in the startup of my life.

The universe kindly decided to prove me wrong.

It was in early 2023 that I discovered that there was a shortage for a summer instructor for 15-150, my course which I loved so much, and I reached out to Tom Cortina, the SCS undergraduate coordinator, to see if there was any opportunity. It would be my last hope at achieving the dream I had fostered for so many years.

I obtained an interview with a professor, and watched the days tick down to it with bated breath. I told no one. I was afraid that my dream was so fragile, it would shatter if I spoke about it. I was afraid that it would be taken from me if I dared to hope it was possible.

In the call booth of the WeWork, I rubbed my cold hands together at the conclusion of the meeting. It's funny how so much thought can go into a moment that is over in a flash. I can scarcely remember the words that were said. I can't even remember the professor's face.

All that matters is that, a short twenty minutes after it started, I had verbal confirmation that I would be offered the opportunity to return to Carnegie Mellon, my alma mater, but as staff instead of student. I would be offered the opportunity to return to the fires of the forge that had shaped me, but to stoke it for others instead.

Looking back, the lack of glamour of the scene is funny. There should have been confetti, a shower of lights, or someone waiting to shake my hand in congratulations. It was as anticlimactic as the graduation I never walked at, a year earlier.

But there was no confetti, and no shower of lights, just the quiet fan of my computer as I processed what had just happened to me. The start of my story, it seems, was not beholden to the laws of the innumerate stories that I had read before.

It is there, in the phone booth set to the side of our small WeWork, in the stolen moments between meetings at my 9-5 job, that I was offered everything that I had ever wanted.

Part 2: Why functional programming?

Carnegie Mellon's undergraduate computer science curriculum is known for its rigor, comprehensiveness, and in certain ways, its unorthodox approach.

This manifests in several key ways, such as:

- Emphasis on theory over engineering and hardware

- Focus on parallel time complexity and parallel algorithms

- Focus on functional programming

The first two points are fit for exploration by a different blog post, but the third will be our focus.

Functional programming is typically taken as the second or third course (depending on the student's previous computer science background) of all computer science majors at Carnegie Mellon. This contrasts to other universities, where the topic would either be an elective, or possibly not even offered.

I first encountered the subject as a freshman cognitive science major in 2019. I knew I was in for something special when I didn't need my computer for the entire first lecture.

The professor started talking about how we were going to learn about "ML", and I remember looking around, wondering if I had joined the wrong classroom. What was this language, "Standard ML", that were learning, and why had I never heard of it?

I took out my computer. Surely we were going to use them. Surely, in a programming class, we were going to be doing some computer programming.

The professor, instead of pulling up a terminal or text editor, pulled out a sheet of paper and a desk camera. He told me he was going to teach us types, and that they were going to be the most essential part of my computer science education.

Critics of functional programming sometimes speak of its perceived esoteric

nature, the detriments of learning a language that one would never actually

apply in the "real world". They speak of the unnaturality of seeing the keyword

let, and how function names should never be separated by a space from their

arguments.

The perspective taken by CMU is that courses do not teach languages. Courses teach concepts, and the languages come after.

Some programming courses are about the syntax. They are about how to write the words of a program, and hopefully with a little bit of luck and elbow grease along the way, a correct program will be produced. The meaning of what is being written, and the concepts that those words map to, are of secondary concern. In the post-LLM world, this is an approach that all of us are familiar with the drawbacks of.

15-150 was one of the first courses I took where it was apparent to me that programming is about the semantics. It is far more important what goes in your head, what high-level constructs you create when decomposing a system and devising a solution, than any characters or concrete details that you render into text.

I embraced functional programming because, for the first time, I felt like I was given a system which encouraged me to articulate my thoughts and solve first, program second. Silly mistakes that would normally be fatal were prevented by strict type-checking, nudging me to revisit my assumptions. A rich type system offered me the tools to architect my solutions at the high level, then work downwards.

In the previous semester, I had participated in a hackathon, where my sole

contribution was struggling to write a basic recursive graph search in Python.

In it, I spent at least an hour debugging my function, which kept returning

None at me no matter what I tried, even though I didn't even think that it

should be possible. I thought that recursion was to blame for my inability.

After 150, I realized that what I had mistaken for an inability to do recursion was simply a lack of elementary reasoning about my program's inputs and outputs. This may seem seem unrelated to functional programming, but ultimately it's the perfect skill that can be trained by the paradigm, because it's precisely what functional programming is about--safety and correctness.

I have four main reasons why I think that people are often opposed to learning functional programming.

- They didn't learn it in school, and feel some perceived esotericity or exclusivity--functional programming is a club, and they weren't invited.

- They believe that it is too complex, or they that they lack some innate aptitude to do functional programming, like it is a talent gifted to few that are fortunate.

- They believe it has marginal benefit.

- They are David Heinemeier Hansson.

Some have approached me with the second and third points.

Over my years of TAing the course, I found these statements hard to justify. I couldn't believe people's claims that functional programming was simply too difficult, too advanced, when I had seen 18 and 19 year olds master it with flying colors for years.

I couldn't believe that it was some unimportant, optional side detail in a computer science education, when I had seen how transformative of an effect it had on students' perspectives and abilities.

Although I was suspicious of these claims, as a TA I was operating in a role that was an accessory to the learning process. I was a helper, and although I had my opinions, I did not feel like I had the authority to challenge them on a broader level.

I needed to be an instructor for 15-150 because I had to challenge these statements myself. I had to see for myself that they were false.

Part 3: On running a course

Themes

One of the first things on my mind was how to make my iteration of the course memorable.

I find that I often forget the details of a course, once it has ended. If it's not something that I will exercise regularly once the course concludes, it's usually something that will be wiped from my mind within the next year, unfortunately.

However, what do I remember from those courses? From courses whose content have all but escaped me, I still remember some of the big ideas. I remember some of the flavors of problems that I had to solve for my probability course, even if I can't do any of the math anymore. I remember the vague impression of an undecidability reduction proof. And most of all, I remember the themes.

It's like when you try to recall a story, and you can't remember the precise plot details, but you can remember the morals that you were supposed to take away. I'm a storyteller by nature, and I couldn't help but think of my course in the same way. I was going to tell a story over twelve weeks, and I needed that story to be cohesive. I needed that story to be engrossing.

So, it was with this understanding that I spent the first two weeks of planning coming up with learning objectives, concrete statements of fact that I wanted students to take away from the course. Then, I put them all together and started drawing lines between them, in a way that is not dissimilar to completing a picture by connect-the-dots. I wanted to find the overarching ideas that permeated all of them.

I came up with the following three themes:

Recursive Problems, Recursive Solutions

Programmatic Thinking is Mathematical Thinking

Types Guide Structure

The important idea here is that these ideas are permanent. Many courses in my life I have taken and immediately discarded, used for a grade and then immediately forgotten about. Sometimes, that's just how it is. But my role as an instructor was to show students that 15-150 was not one of those courses -- that these ideas are fundamental, that they will stay with you for the rest of your life.

Design

It turns out that, in terms of the stylistic design that went into 150 for this semester, I had so much to say that I decided to fold it into a completely separate blog post. You can read it here.

Lessons

The most important part of this entire blog post is the lessons to be taken away from it. What did I learn over the course of those twelve weeks?

Care does not scale, but it sure makes the difference.

I have never been one for bureaucracy. One reason why I enjoy working at a startup is being able to know everyone's name and not feeling confined to a box. Whenever I feel like process or red tape is taking precedence over treating people as humans, it frustrates me.

With this perspective, I decided that I would offer my students as lenient of an experience as I could. The end goal of a college course, above all else, is that students learn -- I tried to focus on this beyond anything else, and do whatever it took to get my students there, even if it didn't exactly align with traditional course policy.

So this semester, I granted every single extension that anyone ever asked me for. My reasoning was that, since most of the learning in 150 happens from doing the homework assignments, if a student doesn't receive an extension and doesn't finish the rest of it, they aren't learning.

The practical effect is that I had a lot of people ask me for extensions. At times it would frustrate me that students were continuously asking for what felt like a deluge of extensions. Was I doing wrong, by granting so many of them? Were students exploiting my leniency for some nefarious ends?

The thing is, I think that this kind of thinking can benefit from a derivative of Hanlon's Razor. Never attribute to malice that which can be attributed to... well, anything else. My frustration was in the thought that students were somehow deliberately asking for too many extensions, or were taking advantage of my leniency, but the point is that students aren't the enemy. It's not a black-and-white, adversarial kind of thing. This kind of reasoning just came out of exhaustion and self-doubt. It solves precisely zero problems.

So I don't regret giving out all of those extensions, because at the end of the day, I don't believe you can ever really doubt a student's reason for asking for an extension. If a student needs help, they will ask, and it's not on you to validate whether it is legitimate. The point is just to set up students for success, not to constrain the conditions under which they can.

There's a "but" to this section, however. Due to all the extensions I gave, keeping on top of all of them was a real struggle for me. Sometimes, I would grant an extension, and have to track down their submission for the assignment, placing more of the onus on myself than the student whose work it was. Although I don't regret being lenient, it was extremely draining on me. Fifty students was already the maximal amount I could deal with, while attending to each personally. Scaling up this kind of treatment would be untenable.

So for professors who teach hundreds of students at a time, as a student I might have not understood why they adhered to strictly to policy, or were seemingly hard on me for no reason, but it takes a more nuanced perspective to realize that, really truly, instructors have a hard job. It's still possible to care for every student. But it's not possible to grant hundreds of students the same level of attention that I was able to.

Failure is expected.

Or, more accurate, some failure is expected. This isn't a claim that it's OK or desirable that there should always be some students who fail a class--I do believe that the objective of a class should be that every student passes.

This is more of a commentary on my experience as a first-time test-writer. While 150 TAs are offered an unparalleled level of power to control the assignments of the course, it is the custom that professors are fully in charge of writing the examinations. This being my first time as an instructor, this was also my first experience with writing an examination.

Several times during the semester, I would write a problem which I thought to be eminently reasonable, only for students to not perform as well as I would have hoped. I confess that this caused me quite a deal of depression. Was I failing as an instructor, for failing to prepare students for what I judged to be a relatively simple problem?

I believe that there are a few things which are responsible for this. For one, although I was closer than most instructors, it is very difficult to remember what it is like to learn a topic for the very first time. Even problems which I judged to be "no big deal" were often still written by myself to be interesting, meaning some non-trivial, non-synthetic problem.

In normal test-taking constraints of only an hour or two, the effort required to problem-solve is highly variable. It is ultimately a stressful environment which I hadn't helped with my focus on writing somewhat more difficult problems.

At the same time, it is not realistic to expect that every student excels. There will always be a gradient, and while it is the instructor's job to ensure that every student gets the base level of understanding from a course, not every student can go above and beyond. Part of my frustration, I realized, was in the fact that I desperately wanted every student to excel.

This is a lesson that I had to learn as the semester went on, where I began to realize that it wasn't realistic to place my standards so high, for my students or for myself. It's no use crying over spilled points.

Students will succeed and students will fail. All that you can do is try your best to help the student do better the next time.

The proof is in the passion.

I'm a very intense person by nature. The only way that I know how to live my life is to throw myself wholeheartedly into all that which I do, and to believe in it so strongly that I cannot imagine anything else.

From the first day of planning, I always intended to make this apparent to my students. The majority of my time as an undergraduate in college lectures, I spent asleep, due to a combination of irresponsible habits and a troublesome lack of belief in the material. There were professors who certainly did a good job at conveying this belief, but some classes I just couldn't bring myself to care enough.

As I wrote in a meme I made for the course years ago as a TA, 150 is not a spectator sport. I could not afford to have my students have that same lack of faith, at least not without trying my best to convince them that not only was what they were learning important, it was essential. I truly do believe that with every bone in my body.

What I mean to say is that I believe that there is an equal and opposite reaction. Something pushed, pushes back. When you speak, somebody listens. When you put effort and energy into the material, I believe students are more likely to do the same in return.

So, every lecture I would arrive with a lesson plan and the energy and enthusiasm to see it through. I focused (sometimes at length) on the motivation and story behind every piece of content, so that not only would students learn the material, but hopefully be able to rederive why it was important.

I think that teaching is multifacted, by intrinsic loss of information. A lecture is the result of hours of compressed time, hours poring over examples and learning materials, and distilled into words meant to fill an hour-and-a-half interval. The compression is lossy in two respects--you cannot expect a student to recover the context of the original material, and you cannot expect a student to remember every rapid-fire word that is delivered.

As a result, I believe that an instructor's job is not to 100% convey all of the information to the student in the limited time of the lecture. It is also to give the student the drive and motivation to seek out the answers to the parts that they did not understand. It is to give the students the power to teach themselves.

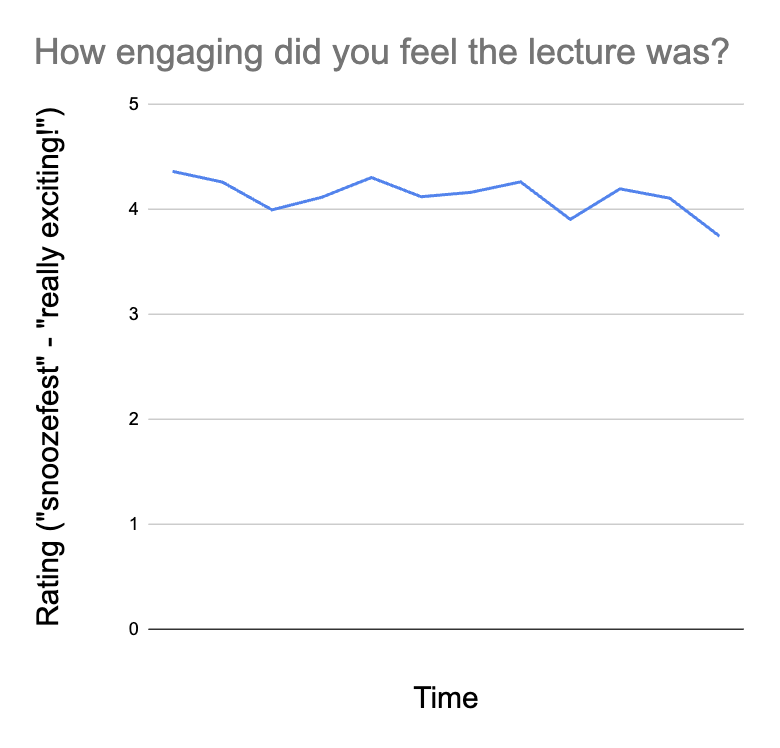

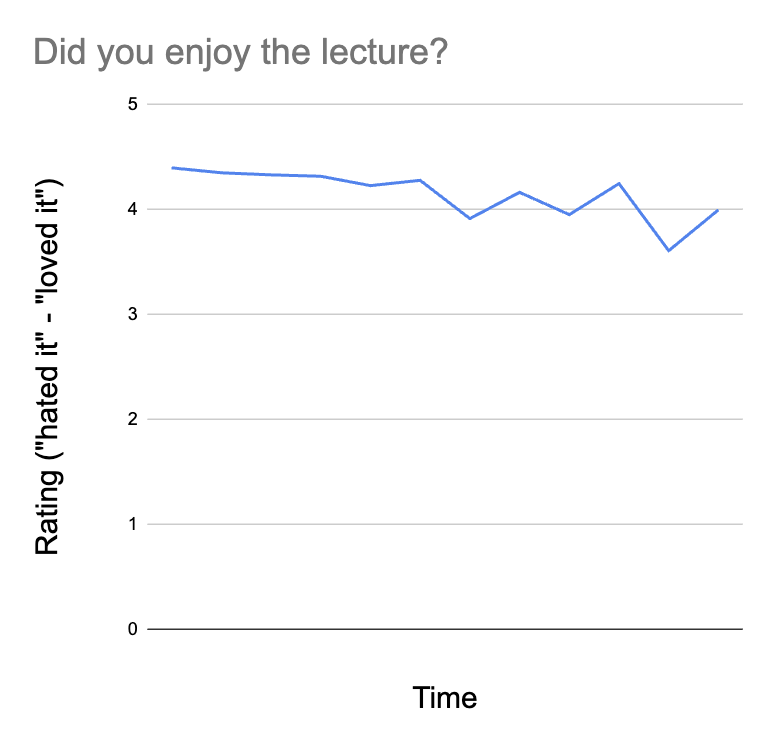

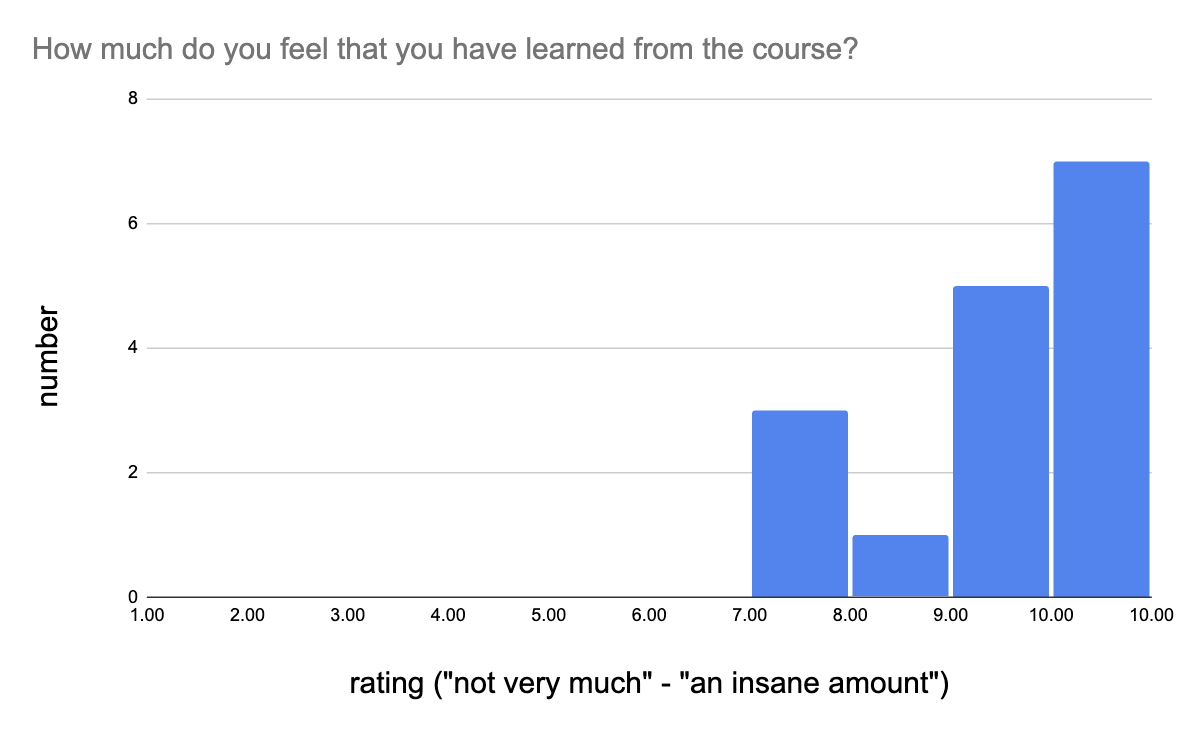

Throughout the course, I have collected feedback in the form of post-lecture surveys and the official course evaluations that students leave at the conclusion of the class. Some of the post-lecture data is pictured below:

Consistently, students have left me messages and emails expressing appreciation for the effort and passion they can see in the course, as well as for the desire for learning the material that it has inspired in them.

These messages are among my most treasured possessions. I have saved each one.

The worn path is not always the right one

The focus of Part 2 of this post was on why it was so important to me to not only teach, but to teach functional programming in particular. How did it match up to what I believed?

Over the course's tenure, I faced the stress of working my job as an instructor concurrently with my job as a software engineer, the looming deadlines of upcoming lectures that I had not yet written, and probably the least sleep that I have ever gotten in my life, including my years as an undergraduate. Despite that, once the course got started, never once did I feel stress over the material that I was teaching to my students. Never once did I feel doubt for whether what I was teaching was right.

The quest of teaching is one which is highly variable, for many reasons. There is intrinsic variance among instructors and subject matters, but most importantly, it is heavily dependent on the students that are being taught. I had the fortunate experience to be teaching students who were not only open-minded and receptive, but willing to grace me with their stories of how the course had affected them.

A classroom can feel like a rather impersonal affair, with a group of people judging your words at a distance. Throughout the progression of a course, you eventually start recognizing the faces, remembering the names of those you see, but it is still a one-sided conversation. There is no built-in feedback mechanism from your students.

I frequently hosted post-lecture office hours precisely for the purpose of not only helping students, but so I could hear their perspectives on their education, their lives, and so I could offer them help in whatever ways I could. Some of the most valuable memories I have occurred in those office hour sessions.

I recall regulars who would drop by my lectures just to chat, students who would come for one-on-one assistance that they felt self-conscious about receiving otherwise, and a student who told me that they called their mother about the class, telling her how excited they were about what they were learning.

I recall a student who had taken the course before, who didn't feel like they had gotten it until now, a student who told me that what they learned in 150 changed their perspective on computer science totally, and a student who told me that 150 made them want to start doing computer science.

I recall a thoughtful email from a student at the conclusion of the course, confessing they had never done so before, but wanted to tell me how much they felt 150 had made an impact on their academic career.

All these stories are not to boast, but to simply say that from day 1, I have never had the impression that the course material was something which had little impact on a student's success or way of thinking. Based on my students' performance on exams and assignments, I have never had the impression that it was simply an inherently complex topic that could only be taught to few. I have never had the impression that there was only an inconsequential benefit.

I find that, when giving opinions on functional programming, people love to cite the path that is well-traveled as justification for its superiority.

I teach and feel passion for a niche topic. I may not succeed at convincing others of that through an online presence (indeed, that is not the purpose of this article), but I am only here to report that, in all my experiences as an instructor, it has only reaffirmed its importance, to me.

My conviction in the power and importance of that which I teach is not made out of my own beliefs or desires, but shaped from the stories of the students who have expressed so much gratitude at having learned the material. At the end of the day, users are the judge, and I am proud to contribute towards carving out a new path, one which may enlighten students for many years to come.

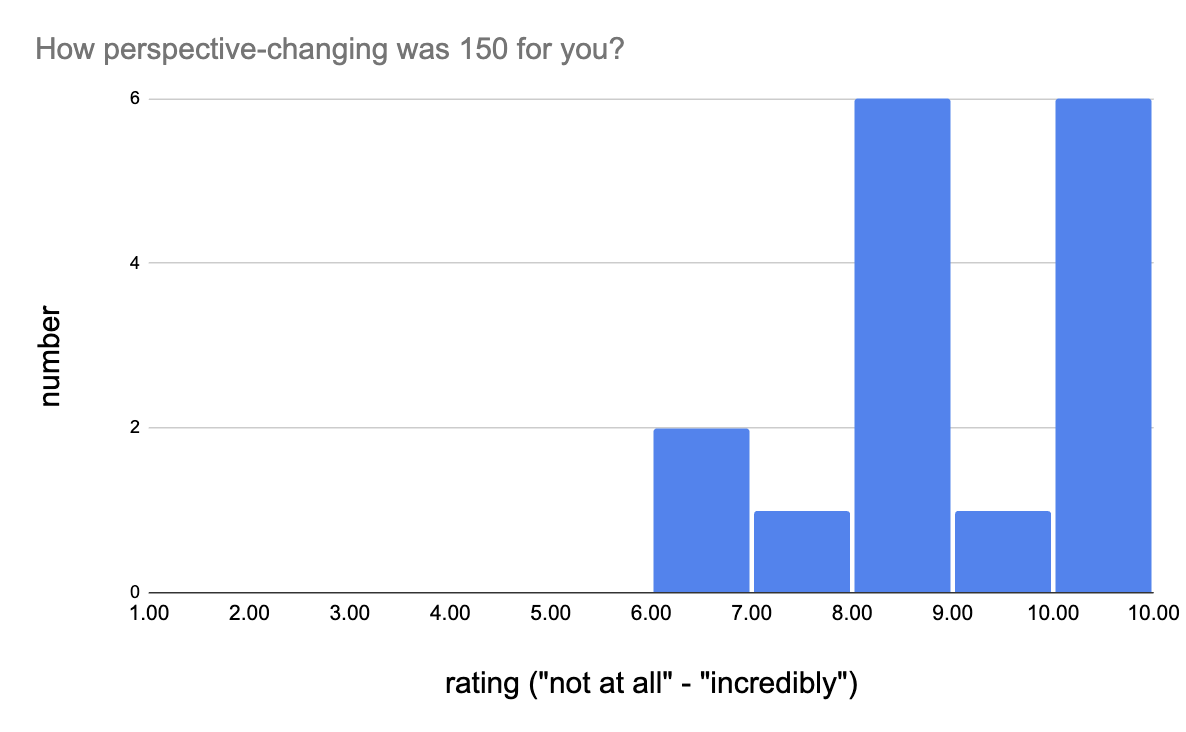

Here are some of the statistics collected from the end-of-course university surveys. The columns indicate, respectively, the number of responses, the proportion of the class those responses represent, and the overall rating the course received, out of 5 .

Glorious Purpose.

I confess an emptiness in my life now.

San Francisco is in many ways a more dynamic city than Pittsburgh, but somehow it feels empty and static. Walking through the streets, my footsteps somehow are louder, the thuds conveying a weight that is not based in mass. Although the Bay breeze blows incessantly, it feels as though the wind has stilled somehow too.

It feels strange to return to a routine, to sleep a recommended amount of hours, and to walk in to my 9-5 job and not feel the existential dread of an upcoming lecture that I haven't yet written. It feels wrong to use my mental energy on tasks that I can make predictable progress on every day, as opposed to sitting in front of my laptop for hours and hours without writing a word, like trying to squeeze blood from the stone that is my brain.

I find that the biggest difference is in the first ten minutes of the day. When I wake up in my bed now, getting out is always optional. There's always another five minutes asleep, another ten, up until the point where perhaps I have missed the train or need to take my first meeting of the day.

Waking up in Pittsburgh was not a decision, it was a fact. Every day when I woke up, I had what can only be described as relentless purpose. No matter how little sleep, no matter what day of the week, I would wake up and be out of bed within thirty seconds, immediately heading out in beautiful sunny weather to my cool air-conditioned office where I would spend the majority of my day.

Some might describe such an experience as hellish, but that summer, I found it exhilarating. There was no "why" to life, it simply was. I continued on not just because I wanted to, but because I had to. No matter how much I was behind, I would find a way to catch up. I would continue to produce content that I loved, lectures that I exulted in, lessons that had real value to my students, because it was just the way that things were. I couldn't have asked for a more meaningful existence. I had found a glorious purpose.

My default state in the summer was to pour my hours into my tasks, and allocate whatever remained to whatever other comforts I desired. Now, I stare into an excess of time, served to me on a platter in pursuit of the ideal known as "work-life balance". An ideal that should be achieved, for sure, but it is a sad thing that someone most in need of something is sometimes the least equipped to know how to deal with it.

The hardest thing about graduating from Carnegie Mellon, in my experience, is finding out what to do with yourself with the time that you get back.

I did promise that this section would be about lessons, and I think that this one is one that I am still figuring out as I go. Regardless, I don't think it is an interpretation like "don't work yourself too hard" or "try not to burn out", as good and true as those sentiments are.

I think it's that, for all of us, glorious purpose exists in some form or another, waiting out there to be captured. "Glorious", not in an objective, flashy sense, but in a personal, subjective one. It's not exactly the purpose that I imagined when I was a child (although close), but for all that I'd given up on it, life took me to one anyways.

But unlike a functional program, purpose is not immutable. The fact that I found a new purpose and left it behind does not mean that I must chase it in my mind and memories. Although I look fondly on the memories that I now have, and the content that I have produced, it is with the knowledge that there is still so much for me to learn and do.

Writing this blog post is, in a way, my way of trying to let that time go.

I'll leave you with my favorite post-course message that a student left me:

All of the materials for my iteration of the 15-150 Principles of Functional Programming course can be found online for free, on this website.